FILMS / REVIEWS Norway / Finland

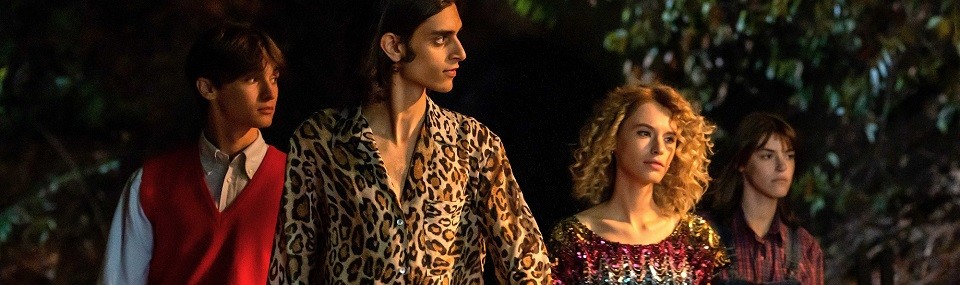

Review: Let the River Flow

- Ole Giæver’s fourth feature tackles Sámi protests and longstanding discrimination with elegant dramatic means

Ole Giæver is no stranger to the festival circuit, with his previous films premiering at the likes of the Berlinale and TIFF. In a way, his position as a filmmaker devoted to telling stories about the human condition in particular Norwegian environments (think of The Mountain or From the Balcony [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Ole Giæver

film profile]) provides a solid footing for more direct, political cinema. Let the River Flow [+see also:

trailer

interview: Ole Giæver

film profile] is his fourth feature and has already been awarded at Tromsø – the director’s home turf – and Göteborg. It now opens in Finland on 5 May, followed by Sweden, distributed by Mer film. One important thing to note is that the movie has already scored not one, but two Audience Awards, which is indicative of the power inherent in its cause and its historical depiction.

Let the River Flow recounts real events that happened between 1979 and 1981 – when the filmmaker was barely a toddler – and which remain a contested chapter in present-day Norwegian history. The so-called “Alta conflict” took place in the northern part of the country, where the richest salmon-producing river is (the Alta). Needless to say, it also provides a livelihood for the indigenous people, the Sámi, and the impending construction of a dam threatens not only their well-being, but also their lives. Giæver crafts a dramatic story around this perilous situation.

In the summer of 1979, Ester (played by Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen, a Sámi musician and activist herself) returns home to Alta to start as a Norwegian teacher at a primary school. She quickly finds herself in a professional and social environment that is not only suspicious of the Sámi, but also openly hostile to them: the conflict has been brewing for a while. Throwaway comments, implicit mockery and unsympathetic silences find her retreating deep into herself and concealing her own ethnicity at all costs, until her cousin Mihkkal (Gard Emil), an ardent activist, intervenes. In the process of educating his cousin, Mihkkal also educates the audience, and with every layer of discrimination and racism peeled off, the film makes an even bolder statement: it’s not all in the past.

While Ester’s journey may seem like a strategically placed stand-in for the viewer’s path to overcoming their own prejudices, Isaksen is well suited for a role that involves a major change of heart. The same goes for Emil, who often brings out the most tragic notes inherent in the struggles of activism when we least expect it. Narrative-wise, the film follows the protests against the construction of the dam through its various stages, including a hunger strike in front of the parliament in Oslo, negotiations, canvassing, and even bigger, pan-Sámi protests: a decision which, given its epic nature, may seem tiresome. But in Giæver’s hands, the realism gels well with the characters’ emotional side.

What is particularly striking about the way the Norwegian filmmaker tells this story of oppression in a lively, empathetic manner is its interpersonal honesty. The film does not shy away from harsh truths or images, or depictions of racism and abuse, but rather counters this emotional weight with balanced, sentimental dialogues. In a heartfelt exchange, Ester and her now-estranged mother discuss the self-stigmatisation they put themselves through as Sámi. In fact, the film is highly critical of the “Norwegianisation” demanded of the Sámi, which they often had to impose on themselves in order to gain the bare minimum respect. Exposing the brutality of such an assimilation can be a tricky thing to bring up in the discourse of your own country, but the responses to the film are telling. The fights of the Sámi do not go unrecognised, but they are far from over, as Let the River Flow warns us.

Let the River Flow was produced by Norway’s Mer Film in league with Finland’s Oy Bufo Ab. Beta Cinema has the international rights.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.