Ena Sendijarević • Director of Sweet Dreams

“It's my job to learn, to educate myself and to try to understand more about this world through cinema”

- The Amsterdam-based Bosnian director gives us the low-down on how she made her idiosyncratic period film and discusses the role of the past in the present

After winning the Heart of Sarajevo with her feature debut, Take Me Somewhere Nice [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Ena Sendijarević

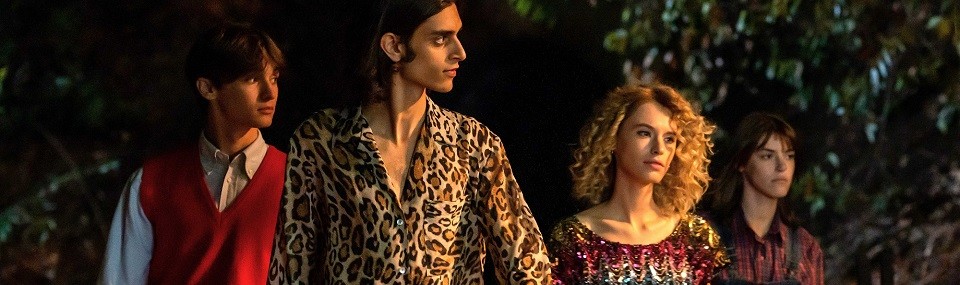

film profile], Ena Sendijarević has presented her sophomore film, Sweet Dreams [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Ena Sendijarević

film profile], in Locarno’s International Competition. The movie is set on a remote Indonesian island, sometime around the year 1900, when the colonial era was already slowly heading towards its end. We met up with Sendijarević after the premiere to discuss the process of making such an idiosyncratic period film and the role of the past in the present.

Cineuropa: Both Take Me Somewhere Nice and Sweet Dreams are in some way symbolic of the past for you, as you were born in the former Yugoslavia and raised in the Netherlands. What did these two returns to the past give you, personally?

Ena Sendijarević: A better understanding of the world, myself and my place in it. We are all dropped onto this planet, and then we try to make sense of it. And you know, the best and the easiest way is through knowledge. And that's why I'm grateful to be, first of all, part of the film industry, but second of all, to be a filmmaker and writer. It's my job to learn, to educate myself and to try to understand more about this world through cinema. But the past is part of the present as well, so I don't see it so much as going back to something, but rather seeing things more clearly. And then understanding where they come from, which involves a change in perspective.

Does your role as a writer-director empower you to revisit these “presents” and to make them yours, in a way?

Well, they are and they’re not [mine] because I'm constantly seeking the right way in, whatever “right” means – so yes, I'm active while doing it, but at the same time, I'm receiving images. You can sometimes also feel more confused because you understand that things are much more complex than you expected. That can turn into an opportunity to make something even better.

As part of your research, you went on a solo trip to various parts of Indonesia. How did this experience inform the film?

I had a guide, and we barely understood each other. It was already interesting to feel like that, being a European woman. Also, the climate had a huge effect on me, as the pace of movement was different because of the heat, and there were insects everywhere. That was fascinating, to really feel how much of an effect it has on your body. So I wanted to take that atmosphere and try to translate it into a cinematic language – to capture that slowness without making it boring. I wanted the sounds of nature to be present, always in the background, and people’s faces to be sweating at all times. We had this spray bottle we’d use literally before every shot! Actually, I had a little wound that wouldn’t heal because of the climate: it got bigger and bigger – it was disgusting. But it had a major effect on me, psychologically, to see how the environment and people’s bodies interacted, especially as I was a newcomer, like my characters.

Coming back to the visual style of the film, it reimagines the past through specific camera angles, lenses, framing and aspect ratios. Can formalism transform the past?

It can give us a different perspective on it, and it can involve the audience in a more contemporary way. If there is a certain kind of freshness or a certain kind of feeling of the here and now in the language through which I'm telling the story, then it will be easier to build a bridge to the past. On the other hand, if you watch a conventional period drama, then it's easier to say, “Oh, that happened then, but now we are past that.”

True – it’s weird that we associate history with something that is old and different in such an obvious way. History is being made every day.

Exactly. And that's why you see that great works of art are always relevant. You read or see them and they feel fresh, and then you understand that, yes, at those times people felt the same way as we do. But if you take a bad piece of art, then it feels dated. And then people say: “Oh, that’s history.” But I agree completely – we haven't changed that much.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.